Blog post written by Mike Raggett.

What makes an opera? According to Dryden’s preface to Albion and Albenius, it is “a poetical tale or fiction, represented by vocal and instrumental music, adorned with scenes, machines and dancing”. So, when did it start in Britain? Let’s find out.

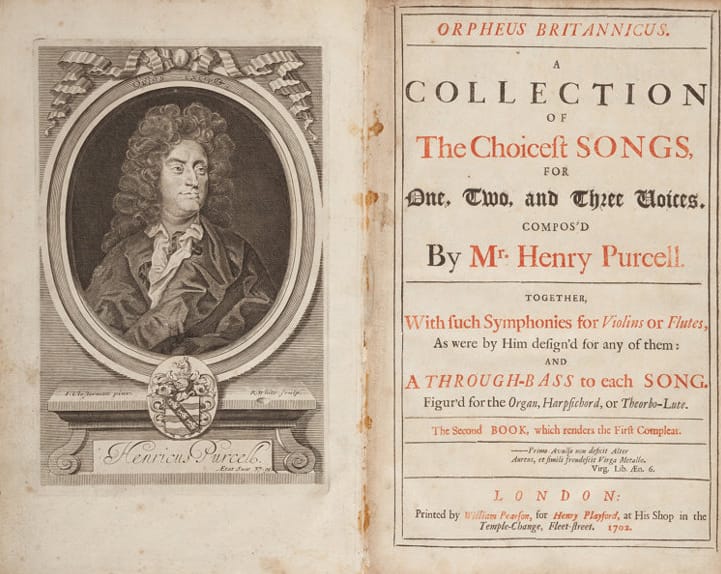

As a friend of the OAE, I’ve been asked to write a few words about the forthcoming concert Restoration Music which Principal Keyboard Steven Devine has developed. It’s a programme of unfairly overlooked music from the seventeenth century when the first English opera was deemed to have been written. In two previous pieces, I’ve looked at the aftermath of the austerity of the Commonwealth and the influence of two composers Draghi and Grabu imported from the continent to spice up the English music scene to the taste of Charles II newly returned from exile in Europe.